EXISTING SUBMARINE DESIGNS THAT COULD MEET CANADA’S NEEDS

By Michael W. Jones, Jim Hughes, John Holmander, and Andrew Miller

June 3, 2022

As the Canadian Patrol Submarine Project considers how to best replace the Victoria-class and deliver the military capabilities that Canada could need in this period of great-power conflict, it might find it useful to understand how well existing platforms deliver those capabilities. Canada’s path to replacing the Victoria class could be easier – both in cost and schedule – if existing designs are able to deliver Canada’s preferred capabilities.

While Canada has not formally announced its requirements for the Canadian Patrol Submarine Project, public comments indicate that Canada’s requirements may include:

- Diesel attack submarine (SSK)

- Operating range of 6,000 nm

- Under-ice capability

- Interoperable with the U.S.’s Virginia-class combat system (leveraging Canada’s prior investment in this system)

- An established, persistent parent navy (to reduce Canada’s in-service support burden)

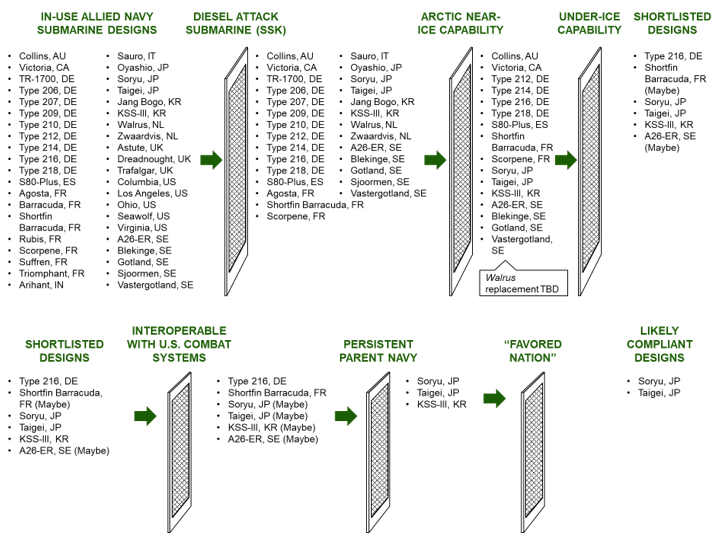

Using publicly available information, we assessed 41 allied navy submarine designs against these potential requirements (Figure 1), identifying 3 submarine designs that could meet Canada’s potential requirements: Japan’s Soryu and Taigei classes, and South Korea’s KSS-III class.

If valid, this assessment has potential implications for Canada’s approach:

- Canada’s potential requirements may not be commonly found together, implying that Canada might need to be flexible on requirements (e.g., under-ice capability, persistent parent navy), willing to engage in a limited-competition procurement (e.g., 1 or 2 bidders), or able to shoulder the design-build cost of a new, bespoke design

- The combination of SSK and under-ice capable is relatively rare – many nuclear submarines can operate under-ice, but not many diesel attack submarines can

- Several potentially attractive designs have not been built (e.g., Shortfin Barracuda, Type 216, A26-ER), and Canada would likely incur additional costs due to first-of-class cost growth and the in-service support burdens that fall to a parent navy

- If only 3 operating submarine designs meet Canada’s potential requirements, there may not be an opportunity to buy a “used” submarine (like Canada did with the Upholder / Victoria), potentially forcing Canada into a more expensive acquisition of new submarines

Figure 1. Comparison of 41 allied submarine designs with Canada’s potential requirements.

Conclusion

It is possible that the requirements that best meet Canada’s needs are a rare combination: few navies need to cover Canada’s extent of Arctic territory, and those that do (e.g., Russia, U.S.) choose to do so with nuclear, not diesel, submarines. Understanding the implication of requirements on available designs could help the Canadian Patrol Submarine Project optimize Canada’s capability needs, schedule requirements, and available budget. Conversely, setting requirements before understanding which existing designs are feasible could put Canada on the same path that Australia recently abandoned: a prohibitively expensive, bespoke, diesel submarine.

Photo credit: The Canadian Press